Lake-dwelling History of Research

The lake-dwelling phenomenon was triggered by fortunate discovery of a lake village at Ober-Meilen on Lake Zurich in 1854. After this first recognition, a frantic search for examples of such material from the Alpine region spread all over Europe. People from many different professional backgrounds started a fierce hunt for those ‘precious’ prehistoric artefacts. At the same time, those prehistoric remains began to be researched by professional scholars. Soon, a romantic image of structures built on stilts above the water surface was conjured up by Ferdinand Keller.

F. Keller's drawing of the lake-dwellings' appearance

Model built to F. Keller's instructions sent to J. Evans by Max Götzinger in 1870

(Click to see the original photograph and letter written by M. Götzinger)

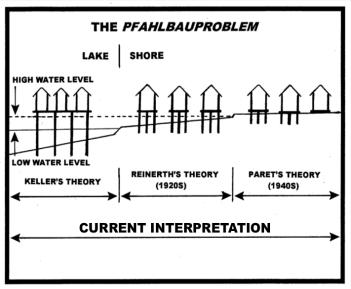

This theory remained unchallenged for more than sixty years, until two main attacks were delivered: by Reinerth in the 1920s and Paret in the 1940s. According to Reinerth, those lacustrine settlements were indeed built on stilts, but not in the lake; they were only influenced by water seasonally. Twenty years later, Paret argued that the lake-dwelling were built near the lake, sometimes on stilts, but they were unaffected by lake-level fluctuations. As a result, Keller’s theory was finally defeated in the 1950s, and the 100th anniversary of lake-dwellings was celebrated by ironically denying their existence. This is known as Pfahlbauproblem (the lake-dwelling dispute).

Recent discoveries supported by scientifically-based excavations have proved that neither of the above-mentioned scholars was wrong. Whether lacustrine settlements stood on stilts above the water, or lay directly on the ground is no longer an issue. A new ere of lake-dwelling research has now begun, with more emphasis placed upon chronology and patterns of occupation.

Current interpretation of the Pfahlbauproblem

New model on display in the John Evans Room at the Ashmolean Museum